The sea had turned gray the morning Evelyn Rhodes began to write again—not storm-gray, not weeping, but a pewter hush, still as breath held too long. It was the kind of gray that made the world feel paused, as if something was lurking just behind the silence, waiting for the right moment to step through. The sky had folded into the ocean until the horizon vanished entirely, as though the earth had erased its borders in preparation for something it could not name. And the gulls—usually raucous, full of fight—now wheeled in slow, uncertain spirals above the cliffs, pale as bone, moving like lost souls unsure whether to rise or fall.

Evelyn stood at the window, her hands curled around a chipped mug that had long since gone cold. She didn’t drink from it anymore. It was a relic, like everything else in the house. Five years had passed since the crash. Five long winters of salt and silence and days so similar they had folded into each other like pages stuck together in a forgotten book.

She had lived alone in the cottage since the funeral. Alone, but not untouched. Time had carved itself into the wood, warped the floorboards, bowed the ceiling. Dust lingered in the air like breath suspended mid-sob. The walls still held the echo of old arguments, laughter, piano notes—things that could no longer be heard but somehow hadn’t fully left. Ivy had crawled up the stone exterior like veins across old skin, choking the chimney, curling over the windowpanes until the light entered in fragments. And Michael’s books—those leather-bound sermons of philosophy and poetry, the annotated margins of a mind that had once believed in something more—still sat undisturbed on the shelves. They were offerings, Evelyn thought, to a god no longer listening. To memory itself.

The accident had taken more than her husband.

It had taken the words.

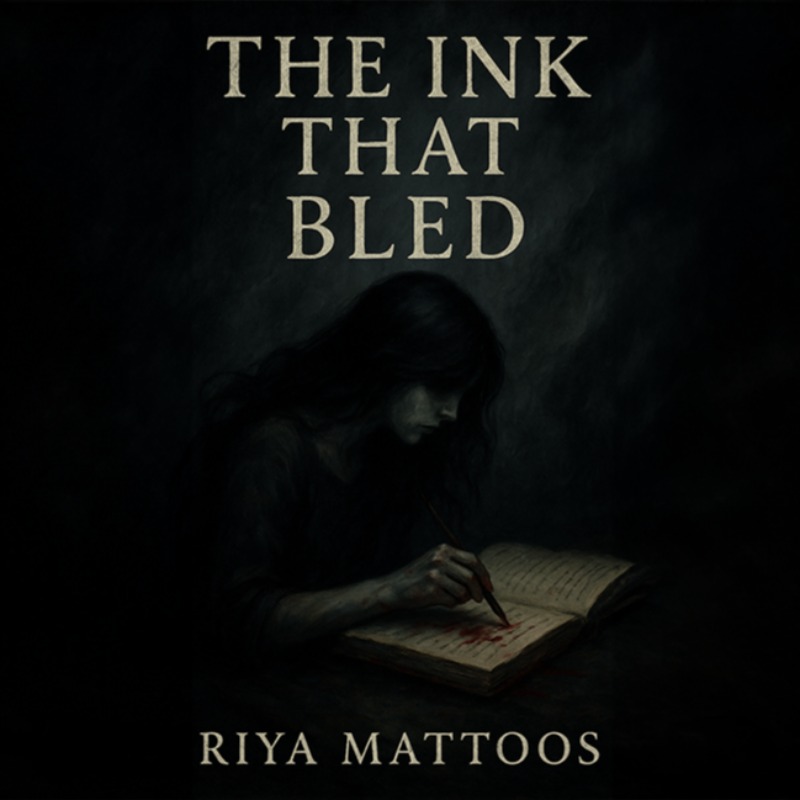

The stories that once poured out of her like rain through gutters had dried up overnight. Her name had once glowed on bestseller lists, filled theaters during readings, circled through whispers at literary festivals. “The woman who sees things before they happen,” one critic had said. “Her prose leaves blood on the page,” another.

But after the crash—after the police report, the shattered windshield, the unanswered questions—Evelyn had stopped. Stopped writing. Stopped speaking, almost. For a while, she wasn’t even sure her voice belonged to her. The pen no longer fit in her hand. Her thoughts no longer formed in arcs and echoes. They just looped, like static.

Until that morning.

She woke before dawn, heart hammering, sheets damp with cold sweat, and the unmistakable taste of something... unfinished on her tongue. It wasn’t inspiration—no, it hadn’t been as graceful as that. It had felt more like compulsion. Like gravity. Like being dragged toward a voice buried deep beneath her skin, whispering from the hollowed places she had tried so hard to ignore.

She hadn’t meant to write.

But her body moved as if guided.

Barefoot, she walked down the creaking staircase, the dim blue light of early morning casting long shadows across the hallway. She passed the front door—the lock rusted, the key long since lost—and made her way to the room she hadn’t entered in years. The study.

It smelled of ink and mildew. A shriveled spider hung from the rafters like a discarded earring. The desk was still there, an antique mahogany piece inherited from her grandmother, the wood scarred with years of edits and ash. Dust coated the surface in a layer thick enough to write her name in.

She sat down slowly, half-expecting her knees to buckle.

The journal lay in the drawer exactly where she had hidden it five winters ago. A gift from her last publisher. Hand-bound, stitched in deep navy thread, with blank pages as pale as bone.

She didn’t think.

She opened it.

And the pen—already resting on the desk, though she had no memory of placing it there—fit between her fingers like it had been waiting.

She wrote a single line. Then another. Then a paragraph. Then a page.

The words came as if dredged from a dark reservoir, fluid and fast, unspooling images that pulsed with tension. A man running. A girl missing. A town smothered by secrets. Each sentence slid into the next with the terrifying clarity of memory, as if the story had always existed, just waiting for her to find the right frequency.

Caleb Stray knew he was being watched.

The cult didn’t leave loose ends.

And the town of Black Hollow had secrets far older than sin.

She wrote until the light changed, until the gulls had gone quiet, until the sea no longer looked like water but like steel pulled taut.

Then she looked down and realized her hands were shaking.

Something had started.

And somewhere, deep inside her—beneath the grief, beneath the years, beneath the silence—something had stirred awake.

She had found herself sweeping the dust from her grandmother’s old writing desk without meaning to. She brewed tea she wouldn’t drink. She opened the leather-bound journal gifted to her on her last book tour. The pen had moved before thought could form.

Caleb Stray knew he was being watched.

The cult didn’t leave loose ends.

And the town of Black Hollow had secrets far older than sin.

Her fingers trembled, but the words remained steady. The story had spilled fast, the images vivid, characters familiar—too familiar, as though they’d been waiting just behind her eyes all along. Caleb: a weary man haunted by names he’d forgotten how to forget. Lena Orrow, nineteen, with auburn hair and eyes like extinguished stars. A town that whispered through doorframes and carved symbols into frost-bitten windows. A phrase had emerged like a breath: The Circle of Red.

She had written until dusk wrapped itself around the sky. She might’ve continued had the cold not crept up through the floorboards and reminded her she was still flesh.

The kettle had long gone cold. Her spine ached. She turned on the television more out of habit than curiosity. Static, then the news. Another case. Another girl. Her tea paused mid-sip.

“—identified as Lena Orrow, nineteen, found at the edge of Marrow Pines, near a series of strange symbols carved into bark…”

The cup had shattered as it hit the floor.

She had stumbled back, gasping. The name. The age. The scene. All pulled directly from the pages she’d written hours ago. She flipped through them with trembling fingers, as if hoping the ink would have vanished. But there she was.

Lena Orrow’s body was left beneath the white pine.

Her mouth was still smiling. Her eyes were not.

The shock dulled slowly, like a scream muffled by fog. She didn’t sleep that night. The wind clawed at the windows, and the sea moaned like something remembering pain. At some point near dawn, she had locked the journal away in a trunk, convinced she’d imagined it all.

But the next morning, the pen was already resting on the open page. Another line had been written in handwriting that matched her own—only her fingers ached as though they’d been writing all night.

The killer was clever, but he left pieces behind.

She moved through the day like a ghost. The kettle screamed. The gulls screeched. And she realized, with growing dread, that she could not remember writing the line at all.

It was only two days later that she met Caleb.

The knock came just before dusk. She opened the door to fog, sea spray, and a man standing in a soaked wool coat, rain dripping from his lashes.

“Evelyn Rhodes?” he asked, voice careful, gentle.

She hesitated. “Yes?”

He removed a glove. “My name is Caleb. Caleb Stray.”

She froze.

He looked exactly as she’d imagined him. Mid-thirties. That quiet sadness behind the eyes. A scar above his brow shaped like a crescent moon. His presence wasn’t startling. It was familiar.

She let him in without knowing why.

They sat at the kitchen table, the light low, the silence louder. He studied the way her hands shook.

“I know how this sounds,” he said. “But I think you’re the one writing my life.”

She blinked, not comprehending.

“I started having memories that weren’t mine,” he continued. “I knew things—names, moments—that I’d never lived. I see things before they happen. And I read words before they’re spoken. I don’t know why I came here, but I had to.”

He reached into his coat and unfolded a crumpled page. Her handwriting. Fresh ink. Words she had not written.

Caleb confronts the author. He begs her to stop writing.

“You’re killing us,” he says.

“I didn’t write this,” she whispered.

“You did,” he said. “Or something did. Through you.”

She wanted to deny it. She wanted to run, scream, cry, burn the journal. But she could feel it—deep beneath her ribs—the story had already burrowed in.

“It’s like… like I’ve become a pen,” she said softly. “And something else is doing the writing.”

He nodded. “I think it wants something. I think it always has.”

More people began dying. Evelyn stopped using ink, but the words still came—etched into frost on her window, burned into toast, scrawled in chalk on the stone path to the cliffs. Sometimes, they’d appear on her skin—faint black letters just beneath the surface like veins. She began to dream in sentences. She'd close her eyes and hear typewriter keys clicking in her skull.

Caleb stayed. Not always inside the house—sometimes she’d catch him down by the shore, staring out at the water, speaking under his breath. He changed over the weeks. Grew quieter. He began asking her questions that felt more like riddles.

“Do you think the story can rewrite itself?” he once asked.

“Maybe.”

“Then maybe we can rewrite the ending.”

They tried. Evelyn penned a version where Lena lived. Where the cult was disbanded. Where Caleb escaped the Circle of Red and disappeared into a new name. But the words never held. The moment she looked away, the ink re-formed itself.

Caleb died under the white pine.

Eyes open.

Mouth open.

A question still bleeding.

One night, Evelyn found him in the attic, staring at the open journal. Blood was smeared across the page like ink.

“I didn’t do this,” he whispered. “It wasn’t me.”

She stepped toward him carefully.

He turned to her. “I think the story’s trying to get out.”

She remembered what he’d said that first day: It wants something.

She began to wonder if it had ever wanted anything other than her. Not her words. Her.

One morning, Evelyn awoke to find every mirror in the house blacked out.

Not broken—blacked out. Each surface that had once reflected her face was now veiled in an inky darkness, as though the glass had swallowed light itself. It wasn’t paint. Not residue. Not dust. The darkness was inside the mirror, rippling faintly like oil on water, refusing to return her gaze.

Every photograph, too, had been destroyed. Torn cleanly in half, the edges too precise for trembling hands. She gathered the pieces in silence—her wedding photo with Michael, her childhood snapshots, even the yellowing Polaroid of her mother in the garden—and realized they were all torn at the same angle, across the throat. Erased, surgically.

Only one object remained untouched.

The journal.

It lay on the desk exactly where she’d left it, basked in a slant of morning light that shouldn’t have reached that corner. Its leather cover seemed to hum softly, faintly warm to the touch. The gold-pressed corners caught the light and shimmered like the surface of disturbed water. She didn’t open it.

Not yet.

She went to call Caleb—to tell him what had happened, to ask whether he’d seen anything strange, or if he’d done it himself in some sudden turn of fear—but the house was silent.

His coat still hung by the door.

His cup of tea, half-drunk, sat on the windowsill, the liquid long gone cold.

But Caleb was gone.

No note. No goodbye. No sound of the front door ever having opened. Just absence, sharp and immediate, as though he’d been plucked from the fabric of the world mid-motion.

She searched the cliffs, called his name across the wind. She hiked the edge of the forest with a flashlight and raw-throated dread, tracing the places she’d never dared explore at night. But there were no footprints in the earth. No broken twigs. No coat buttons. No signs that Caleb had ever existed at all.

That night, the journal opened itself.

She had not touched it.

The pages flipped with slow, deliberate rhythm, as if an unseen hand turned them—searching. Stopping. Revealing.

The message waited in the center, written in her own slanting script.

Caleb was never real.

Caleb was the question you asked yourself.

Caleb was what bled when the words turned inward.

You are the story.

Evelyn staggered back. Her legs struck the edge of the desk. The room tilted.

She blinked—and saw ink trailing down the paper like veins, branching, pulsing, alive. It seeped into the corners of the pages like blood drawn from too-deep a cut.

The journal beckoned.

So she wrote.

For three days.

Without sleep. Without food. The kettle screamed itself hoarse. The fireplace died. Her skin cracked from the cold. Her nails split and bled, but her fingers did not stop moving. Every line carved from her like bone from flesh. Every paragraph unspooled like a confession, peeling her open word by word.

The pen grew hot in her hand—too hot—but she held it anyway. It scorched her fingertips, branded her with every syllable. She no longer knew where she ended and the ink began.

The story deepened. Turned in on itself. Became a spiral. Caleb’s face blurred. Lena’s voice returned in whispers. The Circle of Red multiplied—seven figures, then nine, then thirteen—until they stood in a ring around her, silent, waiting.

And finally, one line emerged from the storm. Etched across the page with terrifying calm:

The only way to stop it is to name it.

She paused.

And in that pause, something else wrote back.

Her name. Whispered softly, from the ink.

Evelyn.

It echoed inside her like an answer she hadn’t known she was seeking.

She rose from the desk with her heart stuttering in her ribs. Walked toward the hallway mirror—the one nearest the door. The blackness still rippled there, thick and unnatural. But this time, when she looked into it, she saw a shape. Herself. Dim, emerging.

And then she saw the eyes.

Not hers.

Black as spilled ink, and watching.

Her mouth opened to scream—but no sound came. Just breath. Cold, and final.

The journal closed itself behind her.

Days passed before anyone thought to check the cottage.

They found her in the study. Calm. Composed. As though she’d simply stopped moving mid-sentence. The pen was still clutched in her hand, her fingers locked around it. Her body held no wounds. No marks. Her face was peaceful, but her lips were stained dark, like she’d swallowed ink.

Only one word had been written across the final page.

End.

They buried her in the town cemetery, though no relatives came forward. Michael’s family, long estranged, never claimed her. The cottage was sold quietly. Her journals vanished.

Except one.

The manuscript was found beneath her body—bound in leather as black as the sea on a moonless night. No title on the cover. No author listed inside. Just a story.

It was published years later through an imprint no one could trace. No records. No staff. The address, when searched, led to an abandoned press building in Black Hollow—though the town itself no longer appeared on any map.

And yet the book appeared in stores.

No marketing. No campaign. Readers found it tucked on shelves between bestsellers, nestled like a forgotten secret. Some said it called to them. Others said it had always been there.

Those who read it never forgot.

One man claimed the protagonist shared his name—and that he dreamt of the character every night afterward. A woman found pages that mirrored her childhood diary, word for word. A bookseller in Oregon swore that one morning, weeks after closing the final page, a single line appeared in her copy:

The story continues.

Find the pen.

Years later, in another coastal town where the fog swallowed the stars and the sea sang in sleep-tongues, a woman sat at her desk.

The rain tapped gently on the windowpane, a rhythm too precise to be random. The kettle hissed once, then fell silent. Somewhere in the distance, a gull cried—then nothing.

She did not remember buying the journal now open before her.

It was simply there.

Bound in black leather, corners worn, pages crisp. No title. No inscription. Only the weight of something waiting. Her fingers hovered above it with the strange reverence one might show a dream they don’t yet understand.

The pen in her hand felt warm. Familiar. Heavy with something more than ink.

She did not recall picking it up.

But it moved—as if it did.

Her hand trembled. Her heart did not. And the first line she wrote was this:

Caleb Stray knew he was being watched...

The fire crackled once in response.

The fog pressed harder against the windows.

And the story began again.

She blinked at the words.

The name had come too easily.

Caleb Stray.

Not a name she had heard before. Not a name from any book she’d read. And yet it echoed, deep and low, in some buried corner of memory she could not trace.

The pen did not pause. The ink glided, confident.

The cult didn’t leave loose ends. And the town of Black Hollow had secrets far older than sin.

Her mouth parted in surprise.

The sentences were not hers—or rather, they were, but she had not formed them. They bypassed thought, blooming fully-formed in the curve of her hand. Her breath shallowed as she turned to the next page.

The fire crackled again.

The rain stopped.

And for a brief moment, everything was still.

The silence grew so complete it felt engineered. Too symmetrical. Too planned. She looked up and saw, reflected in the dark windowpane, a face watching her.

Her own. And not her own.

The eyes were the same shape, but not the same color. Ink-black, like spilled letters. The mouth unmoving. The skin around it too pale. Too still.

She snapped the journal shut.

The reflection vanished.

But the pen kept moving.

It skidded across the desk on its own, dragging ink into loops and arcs, forming words she couldn’t yet read. Her hands trembled as she pushed it away, knocking the cup beside her. Cold tea splashed across the desk—but not a single drop touched the pages. The journal stayed dry, pristine, impossible.

And then the room changed.

The bookshelves she remembered filling with paperbacks were suddenly lined with volumes she’d never seen before—every one bound in black leather, spine unmarked.

She stood too fast. The chair scraped backward. Her breath fogged in the suddenly cold air.

The desk drawer was open.

Inside, an old photograph.

Faded. Curled at the edges. She didn’t remember ever taking it.

A man stood at the edge of a cliff, back turned, coat flaring in the wind. The ocean was behind him, and the sky above was the color of ash. She turned the photo over. One line, handwritten in faint, feminine script:

We write what remembers us.

Her pulse stuttered. She stepped back. The fire had gone out. The rain had returned. But from somewhere inside the walls, she heard it—the low hum of a voice, not quite whispering, not quite singing. A voice she could almost recognize.

She turned back to the journal.

It was open again.

And the words written now were new.

You are not writing.

You are remembering.

Caleb is watching.

The story is already inside you.

Let it out.

Her fingers itched. Her mind tried to retreat, but her body moved forward, as if guided. She reached for the pen.

A name came to her lips. Not Caleb’s.

Her own.

But it wasn’t the name she’d always known. It was older. Buried. A name that tasted like ink and fire and wind off the sea.

And as she touched the page once more, the pen leapt forward in her grip.

She didn’t stop it this time.

The room pulsed with something like breath. The walls exhaled. The sea, somewhere just beyond the cliffs, shuddered like a thing just waking.

She wrote:

Lena Orrow was nineteen when she died.

Her eyes widened.

She had not meant to write that.

She had never heard that name before.

But now—it felt like a memory.

And from the bookshelf, one book slipped free and fell to the floor with a hollow thud.

She turned.

Its spine was blank.

But she knew what she would find inside.

Because the title was already writing itself on the first page:

The Ink That Bled

React

React

React

React

React

React

React

React

React

React