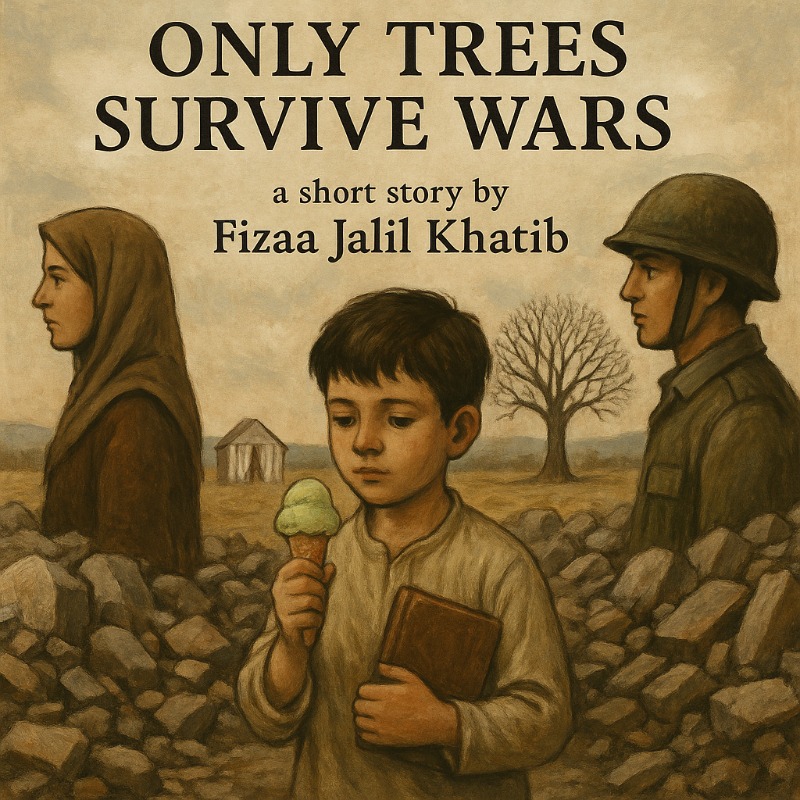

Only Trees survive Wars

A Short Story by Fizaa Jalil Khatib

The war had just ended.

Summer, slipping away, it had been weeks- no, months that he had tasted the cool sweet whisper of Pistachio Swirl, the taste that lingered like an already forgotten memory to a seven-year-old.

“I want it. I want it today. Please, Baba. The boys with those uniformed fathers had it. Why not me? I want it too. I want it too. It’s my favourite ice-cream. I want it.” he cried, pulling the sleeves of his father’s weathered shirt.

The father looked at his equally helpless wife. She picked herself up, almost lost, deaf to the sounds of missiles slicing up the sky, shattered glass raining on the roofs, children crying, mothers as silent as she. Out of made-up reasons, fake promises.

There was no way they could explain the truth to their seven-year-old son of why the other boys could have the ice-cream and he couldn’t. She held her son in one arm and gave him a pinch crushed sugar from one of their cracked jars. The last of it. Sweetest.

“They don’t have this. You’re so lucky.”, she lied with an aching confidence.

“They don’t have you. No Amma. I do”, he cried, hiding in her arms as if warmth could melt hunger and love could dissolve desire. The mother wept in an unbearable silence only her husband could hear.

He was playing with the boys from the family next door, mostly the seeker than the hidden. That day he was convinced to hide, for the first time since his mother has warned him not to cross their side of the street. The game went on, the boys took turns but no one could find him. He was hiding behind the huge old tree on the other side of the field, it wasn’t even far or difficult to spot. But he had lost his way beyond the tree. Slowly wandering off, to his own will.

Eventually, the boys gave up. By the time the game had ended, the sky had turned pink and gold. His mother stood at the threshold, bare of a gate, veiled in two white curtains. She called his name, once, then twice and thrice. She was loud enough for the dead villagers to hear but not the other side of the tree. She didn’t give up, her voice thinning with each call.

He couldn’t hear her.

But he couldn’t hear her. Beyond the tree, everything was quieter. The air felt colder, heavier, as if it had been untouched by sound for a long time. He walked past thorny shrubs and broken fences, past the skeleton of what looked like a home, now a dwelling to the dead. He wasn’t scared, just curious, the kind of curiosity mothers fear- the kind that takes a child too far from home.

He walked for another mile and had entered the place that his mother had called hell, where they lived- The uniformed fathers of happy children, the masked murderers of those on his side. He could almost hear her, her voice breaking, urging him to stop, to turn back.

Though still tempted to find his favourite ice-cream, he turned his back to the place they once called home.

Behind him, a red board stared back, bold and unforgiving: Military Occupied.

But then he started walking again, trying to find his way back home. Darkness had fallen like a curtain, thick and absolute. He could hear only the sound of his footsteps crunching dried leaves beneath him.

Ahead, there was nothing but dark, haunting him like an old forgotten nightmare crawling back under his sleeves. No lights. No voices. No road he remembered.

And then, A tree. It looked like the one he had hidden behind, bullet holes pierced in the same places, branches reaching upward like open arms. But it wasn’t the same. Nothing was. It stood in the wrong place, leaned the wrong way, carried the wrong silence.

He had lost his way home.

Exhausted, he curled beneath its roots and closed his eyes. He missed his mother’s songs more than anything. And his father’s arms, warm and safe. He fell asleep. He watched his parents welcome him into a new home. White and pure as the skies. A beautiful dream had found him.

But peace did not.

He was jolted awake by the shriek of missiles tearing through the sky, by the crack of bullets, the sounds of people who didn’t know whether to cry for themselves or their loved ones.

And in the womb of the war, he stayed still. Small. Silent. Unfound.

The next morning arrived with an announcement only trees and abandoned walls could celebrate.

“The war has ended. We are free.”

He didn’t understand everything those seven words meant, except for the fact that he would be back home, with his parents and would have a lot of ice-creams. He could already feel his mother’s presence in the breeze. He could already taste the Pistachio Swirl on his tongue.

When all the breeze held was blood and death. Rusty, rotten.

He was happy. He understood what freedom meant: Family. Home. Ice-cream. He started walking again. That was all he did since the game had started. He couldn’t bear the hunger anymore. Even at war, his mother fed him well. Two portions, for one. From her plate too.

He walked into the town, crossing the smell of death as if it was normal. Like the dust settled on the streets, like the silence after a scream. He walked through the waves of the dead bodies. There were shoes on the street with no feet in them, the earth looked like a huge quilt patterned with patches of people and their incomplete lives.

He stepped over a doll’s head, her plastic blue eyes staring at the indifferent sky. A little girl’s arm holding onto her father’s shirt, or a piece of it then. There were more people lying dead on the street than the numbers the seven-year-old was taught. He was scared to find familiar faces but all he could see was patches of flesh and blood.

Just a few minutes in, and he could see the ice-cream parlour ahead. No roof, two walls, and the room crowded with dead, cold and red. He entered the room like a usual customer, the man who always gave him an extra scoop for reciting his favourite poem was nowhere to be found.

He stood before the ruins of the world under the open sky, reciting the poem as he scooped the last of the ice-cream left:

“We sleep under the wide blue sky,

He watches over us.

We wake up over the green earth,

He watches over us.

But can you tell if he can see,

What’s a prayer, what’s a plea?”

He wiped his face, the taste of sugar and ash with the back of his sleeve. There, between the counter and last standing wall, he found a notebook. Old, worn in black fabric, its corners curled like old leaves. Strangely untouched, waiting to be read. It survived.

It had no name. Just a few dates. Fourteen days. It was written twelve years ago. As he flipped through the pages, many words rushed before his eyes, all he could catch was:

D-E-A-D,

D-E-A-D,

D-E-A-D,

D-E-A-D,

D-E-A-D,

D-E-A-D,

D-E-A-D.

“Seven dead”, he said.

H-O-P-E,

H-O-P-E,

H-O-P-E,

H-O-P-E,

H-O-P-E,

H-O-P-E,

H-O-P-E.

“Seven Hope.”

The language of war was never meant for the mouth of a little boy. But he did understand: The first seven days had brought her death, the next seven- hope.

He trailed his way back home, fighting the waves of silence and death. There were no more uniformed men, or their children, no more familiar faces. No more missiles, gunshots or cries. Finding a way back home was easier than he had thought. As if something had been pulling him closer.

He was back at the tree again. He realised that had walked almost all around the town. A full circle of being lost and found. Of hide and seek. He walked through the white curtains. Spotless.

“Amma? Baba?”, he cried.

“The war is over. We’re free.”, there was no joy in his voice. There wouldn’t have been until he would see his parents.

“Are we playing hide and seek? I’ve come to find you now.” He said, breaking down in tears.

“I’m not going to hide again. We’ll be together. I’m home”, a loud shriek.

He felt his parents hug him. A final cry. A thud. A gunshot.

The boy touched the ground, “I’m home.”

A young soldier entered the room. Blank. He couldn’t understand what he had done. Blind. He was young. Maybe a teenager still. Pulled into the war. Numbed by the violence of the war.

The wind blew softly. The white curtain moved like a ghost in mourning. It brushed against the soldier’s face, briefly. He blinked.

“This cannot be real. The war is over. The war was over.”

That’s when he saw the notebook. Black. In the little boy’s arms. His blood still fresh, his lips parted as if to call out his parents again. There was no name on the notebook. No name to the boy. “Names don’t matter in wars.” He spoke.

“Shaheed. Shaheed. Shaheed.” he cried. “All martyrs.”

He picked up the notebook. Flipped through the pages. Cried and cried and cried as he read the short entries, the fourteen days.

She had lost all her family to the war. Her little boy the first day, her husband, her parents, siblings, everyone.

In the next seven days, she found little rays of hope. A yellow bird someday, a greener tree, the blue sky. A scoop of Pistachio Swirl. Despite all that she had lost, she tried to live for the love she had, still.

She was about to lose it again. Thinking, she wouldn't survive the war.

"Day 13

If the war doesn't kill me, grief will."

And then-

The last amongst the hopeful days, her reasons to live, was:

“Day 14

The war had quieted for a moment today, just enough for the birds to dare a song. I went out early, looking for water and maybe a little calm, though I’ve learned not to expect either.

That’s when I saw him. A boy, no older than eight, sitting by the rubble of what once was a home. He didn’t cry. Just stared at the ground, like he had already learned what silence meant in a world like this.

I didn’t ask his name. I just knelt and opened my arms.

He came to me.

I bathed him in my rusty basin behind the kitchen. I fed him, just rice and curd and he ate without a sound, without looking up. Later, when I held him, he fit perfectly within my nothingness. An abandoned mother.

He reminded me of my little one. The way his arms wrapped around mine in sleep. The way his breath hitched between dreams. For a few hours, I let myself believe it was him again. Returned.

We played under the mango tree. I pushed him gently on the swing, and he laughed, once. Just once. Then he fell. The swing spun empty while he screamed, clutching his elbow. He cried for what felt like forever. And I, God…I rocked him until the sun had set and left us in a sky of fire and ash.

By evening, someone came. His aunt. She didn’t kneel or smile. Just held out her hand.

He looked at me one last time before he went. No tears then. Just that same silence.

I don’t know if I’ll ever see him again. But today, for a little while, I was a mother again. Not to a memory. Not to a ghost. To a boy who still had warmth in his hands.

I think I can survive this war. He did and he helped me too.”

The soldier’s fingers trembled. The book slipped from his hand, landing open across the boy’s feet. His own scar began to ache.

“The swing. The scar. Her mango tree. How I finally found sleep in her lap after the riots… It was her.”

He touched the scar on his forehead, couldn’t stop crying. It was her. Mama. Not his own mother, but the one who sheltered him after the riots twelve years ago. He was the same age as the little boy he had killed in his blindness just a while ago. She saved him.

“I could have saved him too.” He sobbed as he saw the boy again.

“Did I kill her too? Oh! God. I reek of blood. Oh! God!

He rushed outside. Throwing up his guilt into the roots of a young sapling. The war he thought had ended, had only just begun. Again.

Weeks later, he found himself reading her notebook again. Sobbing into the old brown pages, he wrote, finally:

“Day 1

The war had just ended.

All homes had fallen. All the walls, too. The war never really ends, just wears a new face.

All men fall and only trees survive wars.”

React

React

React

React